Share this

A Thousand-Year Responsibility: Lessons from Japanese Carpentry

by Sean Hill on May 26, 2025

During the bank holiday weekend, I visited Japan House in London and stepped into a world shaped by hand, heart, and humility.

The exhibition, The Craft of Carpentry: Drawing Life from Japan’s Forests, offered more than a display of ancient techniques. It offered a blueprint for how we might return architecture to its rightful place - as a quiet, lasting dialogue with nature. Within moments, I was immersed in a room scented with hinoki cypress, surrounded by full-scale timber joints, delicate ink drawings, and tools so refined they seemed to whisper.

Ceremonial robe worn by master carpenters during shrine and temple rituals - a symbol of the deep spiritual connection between craftsmanship, nature, and tradition in Japanese architecture.

It wasn’t just an exhibition. It was a lesson. A pause. A reset.

1. Listening to the Forest

In Japan, carpentry doesn’t begin with a sketch. It begins with reverence.

Domiya daiku - temple and shrine carpenters - view timber as a sacred resource, not just a structural one. Before trees are felled, carpenters offer a prayer to the kami (spirit-deities) believed to reside in the forest. This isn’t symbolic. It’s practical philosophy.

Samples of Japanese timber species displayed alongside their fragrant wood shavings, offering a sensory introduction to the raw materials chosen by carpenters for their grain, scent, and structural character.

The great craftsman Nishioka Tsunekazu taught that for sacred buildings, timber should be drawn from a single mountain. Trees grown at higher altitudes become columns and beams; those from lower slopes become floorboards or panelling. Each piece of wood is chosen with care and used with intent.

And the line that stayed with me:

“If we use a 1,000-year-old tree, we must be prepared to take on more than 1,000 years of responsibility for the building we create.”

That one sentence has reshaped how I think about every material specification, every client brief, every shortcut we’re tempted to take.

2. The Tools That Shape Culture

Displayed with the gravity of museum artefacts - and rightly so - was the standard Japanese carpentry toolkit. A 1943 survey found that 179 tools were considered essential to construct a full-scale building. In the exhibition, 87 of them were on show. Not flashy. Not digitised. Just deeply purposeful.

A masterfully curated display of traditional Japanese carpentry tools - from chisels and saws to kanna planes and gimlets - each tool refined over centuries to embody precision, purpose, and deep respect for timber.

There was the sumi-tsubo, an ink pot with a silk thread soaked in black ink, used to snap perfectly straight lines. Unlike its Western chalk-line cousin, it is often exquisitely carved, as if the act of marking timber deserved beauty.

Then the suji-kebiki - the marking gauge - used to draw exact parallel lines. And the kiri, or gimlet, a handheld tool for boring holes, long predating the electric drill.

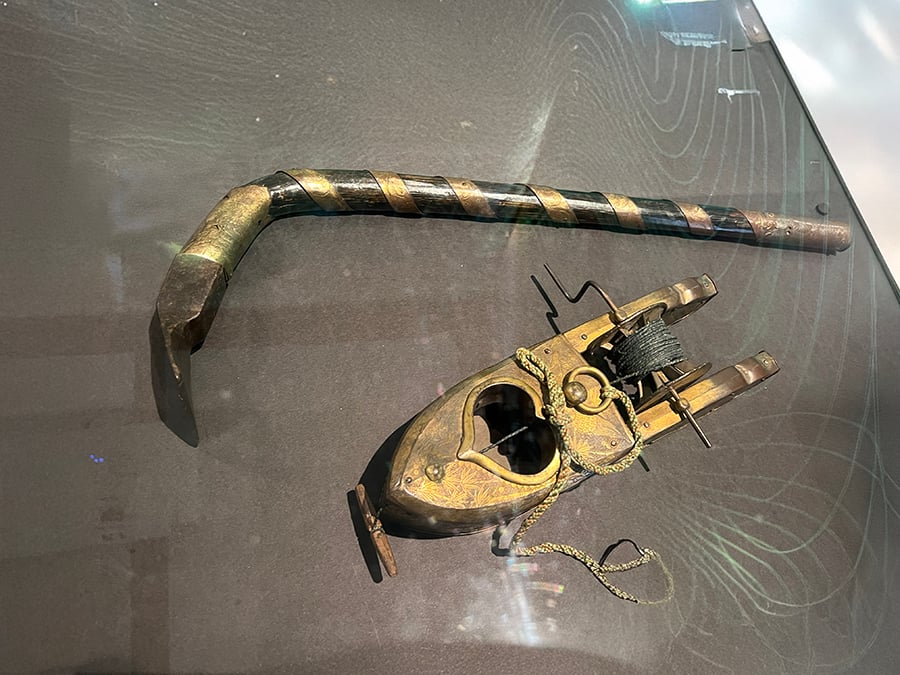

An ornately crafted sumi-tsubo (ink line marker) and crowbar-style tool used by Japanese carpenters, blending functional precision with artistic detailing, and reflecting the reverence given to tools in traditional craftsmanship.

Saws (nokogiri) were thin and flexible, designed to cut on the pull stroke, allowing for greater control and a cleaner finish. Unlike Western saws, which push, Japanese saws respect the tension of the user’s body. They respond. They listen.

Planes (kanna) are also pulled rather than pushed. Some have a single blade, others a double blade - the latter introduced in the late Meiji period to reduce surface tearing against the grain. The difference in finish is astonishing.

Then the chisels (nomi): some for striking, others for paring. Those that take a hammer blow have an iron ring on the handle’s end - the katsura - to withstand impact. Genno, or hammers, come in varying shapes: flat, pointed, and balanced differently depending on the task. Each designed not to dominate, but to serve.

Axes, or ono, come in many forms - each evolved for its task. Narrow-bladed axes are used for precise cutting, while broader axes with an angled edge - known as masakari - are for finishing and shaping timber. Kiri-ono cut through wood fibres; wari-ono split them apart. Smaller variants, like the short-handled kowari-ono, are perfect for splitting timber into smaller pieces. Among the masakari, one version has a long handle for timber processing, while another, the daiku-masakari or carpenter’s broadaxe, is shorter - a rough but reliable companion for shaping wedges or trimming reclaimed wood. Every curve, bevel, and weight balance speaks to the quiet intelligence of toolmaking.

A selection of traditional Japanese axes, including ono (cutting axes) and masakari (broadaxes), each uniquely shaped for specific forestry and carpentry tasks - their forms evolved through centuries of practical refinement and regional adaptation.

Finally, maintenance tools: the whetstones - from coarse (ara-to) to ultra-fine (shiage-to) - used to sharpen blades with the same patience and precision that built the temples of Nara.

These aren’t just tools. They’re an entire philosophy made tactile.

3. Teahouses and the Architecture of Lightness

If temple carpentry teaches endurance, then teahouse carpentry - sukiya daiku - teaches subtlety.

These craftsmen build spaces meant to disappear into their context. Clay walls less than 42mm thick. Round, unprocessed logs used as pillars. Natural curvature embraced, not corrected. Every component shaped for atmosphere, not ornament.

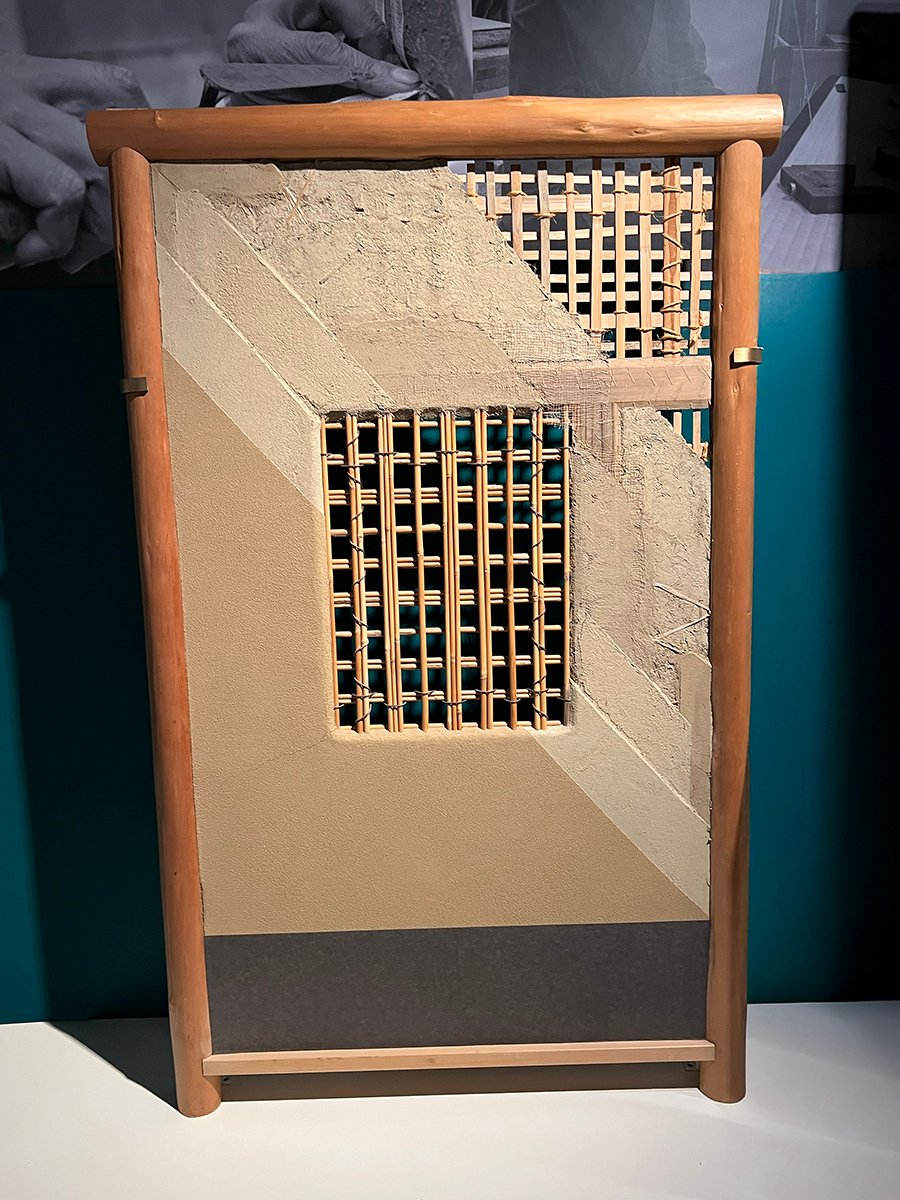

Cross-section of a traditional Japanese clay wall, revealing the layered bamboo lattice (wattle), rope ties, and hand-applied earthen plaster - a delicate yet durable construction method typical of sukiya architecture and teahouse design.

Tatami mats are woven from spliced igusa rush grass, eliminating the fragile tips and extending their life. The border is simple linen - unpatterned, understated. Even the nails - around 100 varieties in a single teahouse - are handmade, blackened with pine smoke, and barely visible once installed.

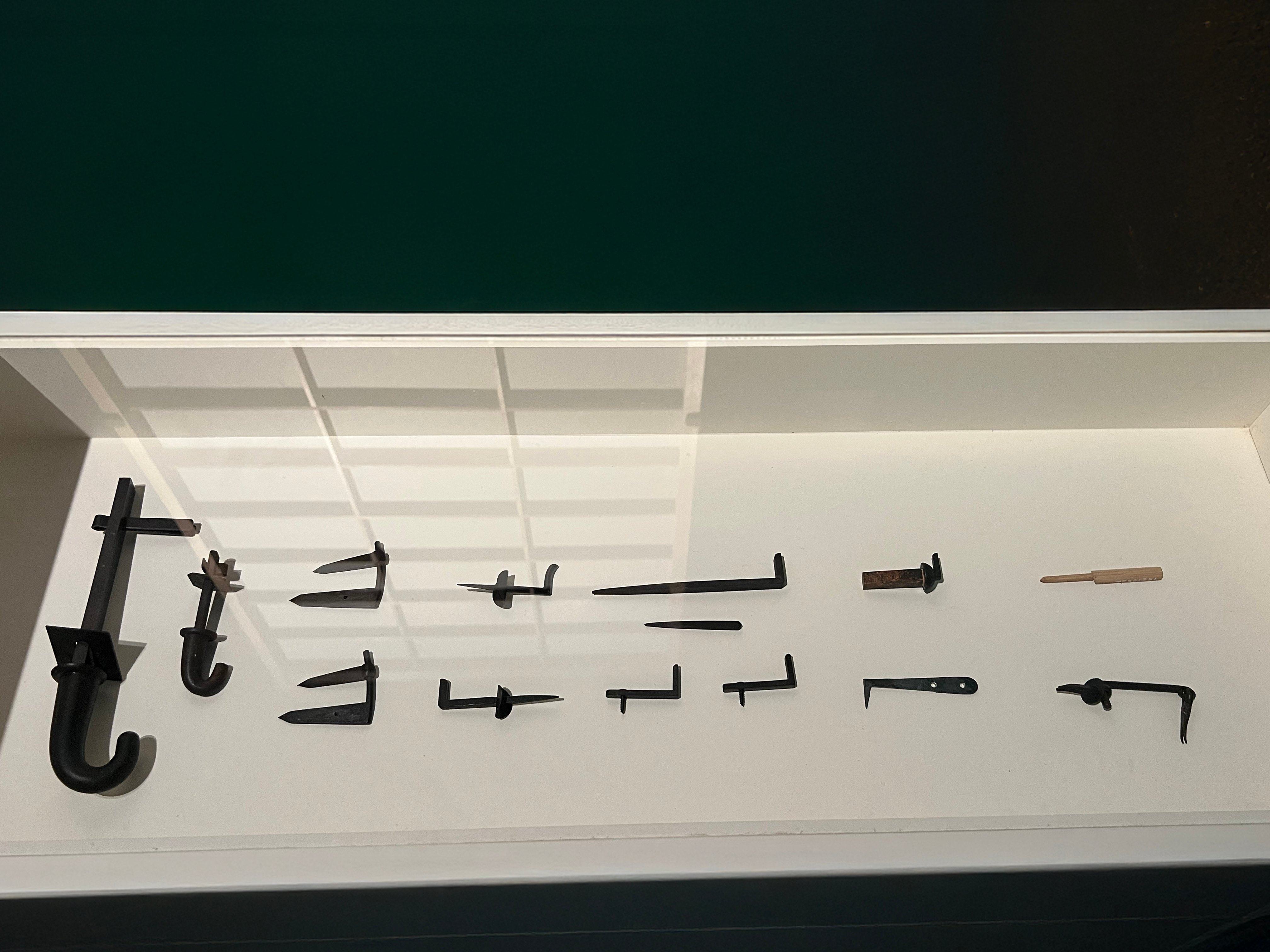

Hand-forged teahouse nails, each uniquely shaped for specific uses - from hanging scrolls in the tokonoma to supporting seasonal flower arrangements. Often hidden in plain sight, these small details reflect the quiet precision and poetic intent of traditional Japanese carpentry.

And then there's hikari-tsuke - the art of shaping the base of a pillar to match the irregular stone beneath it. A practice of patience, of honouring what is there rather than imposing upon it.

I walked through the full-size reconstruction of the Sa-an teahouse from Daitoku-ji temple and felt a deep, almost physical calm. It was a reminder that architecture doesn’t need to assert itself to be profound. It only needs to hold space with grace.

Roof detail from a traditional Japanese teahouse, showcasing finely milled timber boards, bamboo lattice support, and a raised ventilation hood - a quiet example of functional elegance and deep respect for natural materials.

4. The Join as Philosophy

Nowhere is Japanese craftsmanship more astonishing than in its joinery.

These are not just ways of connecting wood. They are codes of ethics.

The neji-gumi joint - a twisted tenon so precisely carved it appears seamless - seems to defy physics. The noge-tsugi, a rabbeted, blind-mortised gooseneck joint, used only in hidden corners. The shiho-sashi, a four-way joint that unites horizontal beams from all directions into a single post - structurally risky, geometrically sublime.

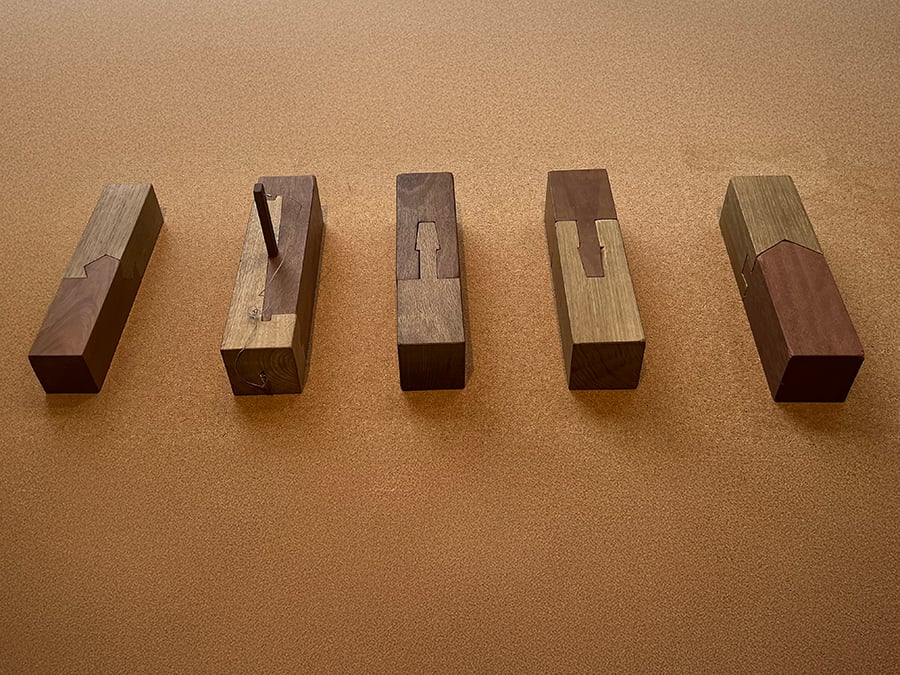

A display of traditional Japanese wood joinery techniques, demonstrating precise interlocking timber joints - crafted without nails, glue, or screws, these examples embody the quiet ingenuity and structural clarity at the heart of Japanese carpentry.

These joints don’t rely on glue or screws. They hold because they fit. Because they’re true.

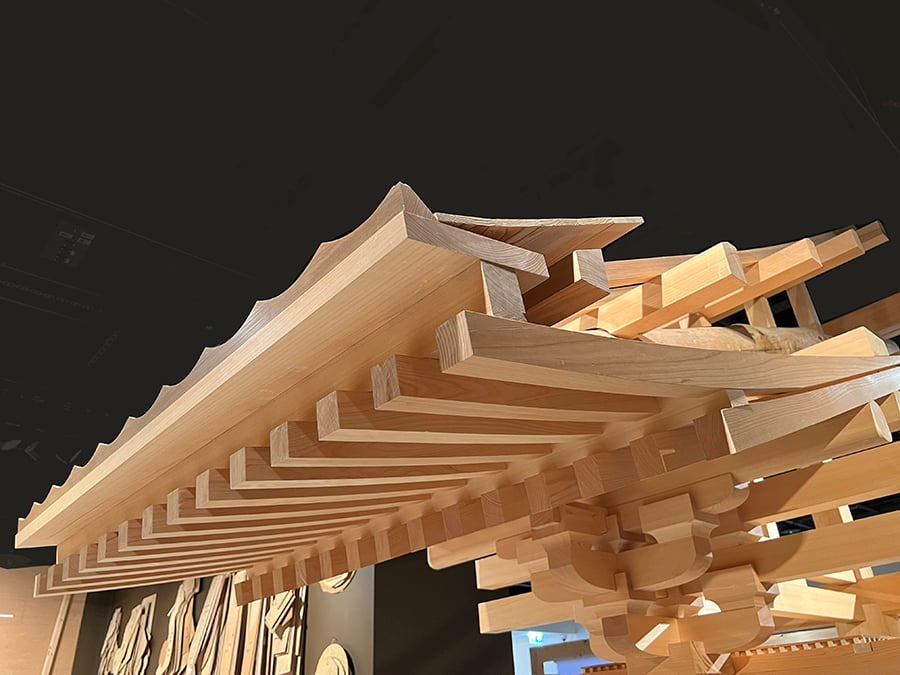

The kumimono brackets, stacked beneath temple eaves, distribute weight like a balanced scale - all in wood, no metal required. Each piece interlocks not just for function but for integrity. The kind of structural honesty that’s hard to come by in modern building culture.

This is craft not as embellishment, but as principle.

5. Touching Time Through Tools

One display showed a full-scale hip rafter (sumi-gi) from Jigen-ji Temple - a structural beam with mortises for inserting rafters at exact angles. The joinery angles require a skill called kiku-jutsu _ combining geometry with a spatial intuition that borders on mystical. You could feel the time it took. The care.

Detail of a traditional Japanese temple roof, highlighting the intricate kumimono (bracket complex) beneath layered wooden eaves - a masterful expression of structural harmony, balance, and craftsmanship without the use of nails.

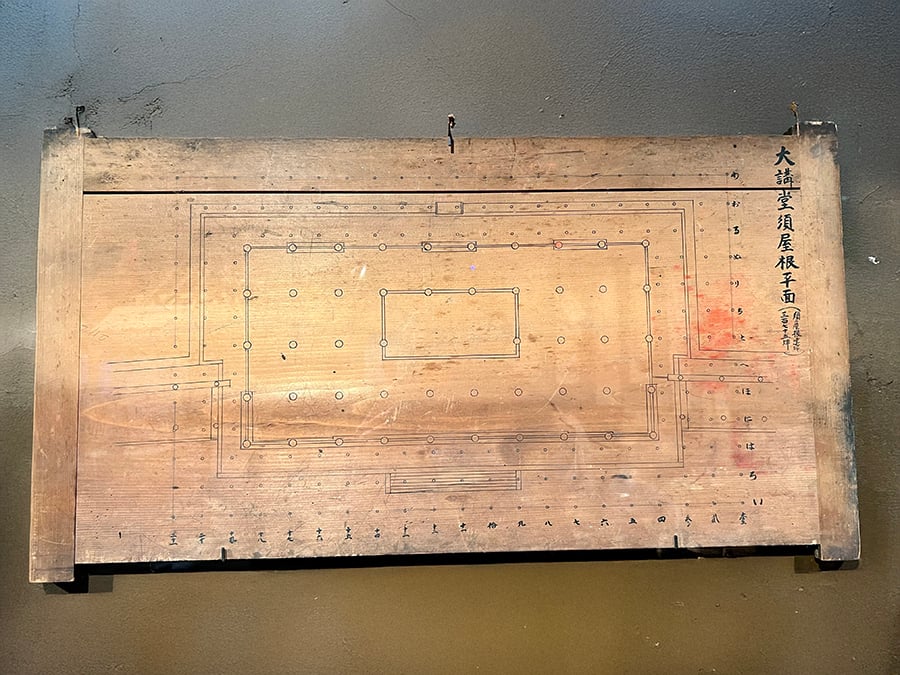

Nearby was an elevation drawing on plywood - not for presentation, but for construction. Done not in AutoCAD (or ArchiCAD as we use in the studio), but in ink and touch, showing the complexity of intersecting rooflines and curved eaves.

A rare example of a traditional zuita - an architectural drawing rendered directly onto a wooden board. Used by temple carpenters before the widespread use of paper, these plans guided the precise layout of structural elements with enduring clarity and care.

I stood and stared at that plywood for a long time.

At RISE, we create digital twins of our projects, fully modelled in 3D. But here was another kind of twin: a hand-drawn memory of a building-to-be. Not abstracted, not flattened - embodied.

It made me think: maybe drawing, like building, should always involve a bit of the body.

6. Reconnecting Practice with Purpose

As an architect, I often talk about sustainability. Energy efficiency. Embodied carbon. But this exhibition reframed the conversation.

Because what Japanese carpentry teaches - more than technique - is care.

Care for materials. For time. For silence. For the user who may never meet the maker. For the land that gave up the tree. For the hands that shaped it.

At RISE Design Studio, we’ve always believed in low-energy, low-carbon architecture. But this exhibition reminded me that sustainability isn’t just about data. It’s about devotion. To making well. To making less. To making things that can last, because they were built with intention.

We don't all need to use chisels and pull-saws. But we do need to ask:

Are we making buildings that deserve their materials?

Will this choice still matter in a century?

Does it belong to its place?

Because true craftsmanship doesn’t just join timber. It joins generations.

And maybe, in a world full of speed and disposability, it’s time we started building like we mean to stay.

We'd love to hear from you.

If you you’re planning a project and would like to explore ideas with our team, feel free to drop us a line at architects@risedesignstudio.co.uk or give us a call on 020 3947 5886

RISE Design Studio Architects company reg no: 08129708 VAT no: GB158316403 © RISE Design Studio. Trading since 2011.

Share this

- Sustainable architecture (152)

- Architecture (151)

- Passivhaus (68)

- Design (67)

- Sustainable Design (65)

- Retrofit (59)

- London (51)

- New build (51)

- Renovation (43)

- energy (39)

- interior design (37)

- Building materials (35)

- Planning (34)

- Environment (31)

- climate-change (30)

- Inspirational architects (27)

- Refurbishment (27)

- enerphit (27)

- extensions (27)

- Building elements (22)

- Inspiration (21)

- low energy home (19)

- Rise Projects (16)

- Extension (15)

- Innovative Architecture (14)

- London Architecture (14)

- net zero (14)

- Carbon Zero Homes (13)

- General (12)

- Philosophy (12)

- Sustainable Architect (12)

- sustainable materials (12)

- RIBA (11)

- Working with an architect (11)

- architects (10)

- Awards (9)

- Planning permission (9)

- Sustainable (9)

- Residential architecture (8)

- Sustainable Tennis Pavilion (8)

- architect (8)

- low carbon (8)

- Airtightness (6)

- BIM (6)

- Eenergy efficiency (6)

- Overheating (6)

- Passive house (6)

- Tennis Pavilion (6)

- Uncategorized (6)

- Virtual Reality (6)

- BIMx (5)

- Backland Development (5)

- Basement Extensions (5)

- Carbon Positive Buildings (5)

- Costs (5)

- RISE Sketchbook Chronicles (5)

- cinema design (5)

- construction (5)

- insulation (5)

- local materials (5)

- sustainable building (5)

- AECB (4)

- ARB (4)

- Feasibility Study (4)

- Home extensions (4)

- House cost (4)

- Paragraph 84 (4)

- concrete (4)

- constructioncosts (4)

- modular architecture (4)

- mvhr (4)

- natural materials (4)

- structural (4)

- structuralengineer (4)

- working from home (4)

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) (3)

- Brutalist Architecture (3)

- Building in the Green Belt (3)

- Chartered architect (3)

- Fees (3)

- Home improvement (3)

- Paragraph 79 (3)

- Paragraph 80 (3)

- Permitted development (3)

- Property (3)

- Social housing (3)

- Spain (3)

- Sustainable Architect London (3)

- Sustainable Extensions (3)

- Sustainable Interiors (3)

- Timber Structures (3)

- backland (3)

- building regulations (3)

- circular economy (3)

- country house (3)

- countryside (3)

- furniture (3)

- listed buildings (3)

- plywood (3)

- sustainability (3)

- sustainable structure (3)

- zero waste (3)

- 3D models (2)

- Architects in Spain (2)

- BREEAM (2)

- Bespoke lighting (2)

- Biophilic Design (2)

- Bricks (2)

- Building energy (2)

- CLT (2)

- Chartered Practice (2)

- Clay Plaster (2)

- Commercial Architecture (2)

- Contractor (2)

- Covid-19 (2)

- Designing with Stone (2)

- Ecohouse (2)

- Furniture design (2)

- Garden studio (2)

- Heat Pumps (2)

- Heritage (2)

- Japanese Archiecture (2)

- Kensal Rise (2)

- Loft conversion (2)

- Low Carbon Future (2)

- Mews House Retrofit (2)

- Modern Methods of Construction (2)

- Period Homes (2)

- Permitted development rights (2)

- Queen's Park Sustainable Architect (2)

- Recycling (2)

- Roof extension (2)

- Social Distancing (2)

- Store Design (2)

- Sustainable Affordable Homes (2)

- Sustainable Architect Fees (2)

- Sustainable Natural Materials (2)

- Timber Construction (2)

- Welbeing (2)

- West London Architect (2)

- Winter Performance (2)

- ashp (2)

- barcelona (2)

- building information modelling (2)

- co-working (2)

- design&build (2)

- epc (2)

- glazed-extensions (2)

- green architecture (2)

- greenbelt (2)

- health and wellbeing (2)

- historic architecture (2)

- house extension (2)

- interiorfinishes (2)

- light (2)

- living space (2)

- london landmarks (2)

- londoncinemas (2)

- openingupworks (2)

- peter zumthor (2)

- project management (2)

- rammed earth (2)

- renewable energy (2)

- self build (2)

- traditional (2)

- trialpits (2)

- waste (2)

- wooden furniture (2)

- #NLANetZero (1)

- 3D Printing (1)

- 3D Walkthroughs (1)

- Adobe (1)

- Agriculture and Architecture (1)

- Alvar (1)

- Architect Barcelona (1)

- Architecture Interior Design (1)

- Architraves (1)

- Area (1)

- Art (1)

- Audio Visual (1)

- Balconies (1)

- Biodiversity (1)

- Biophilic Architecture (1)

- Birmingham Selfridges (1)

- Boat building (1)

- Boats (1)

- Brass (1)

- Brent Planning (1)

- Brexit (1)

- Brownfield Development (1)

- Carpentry (1)

- Casting (1)

- Chailey Brick (1)

- Cold Water Swimming (1)

- Community Architecture (1)

- Concrete Architecture (1)

- Construction Costs (1)

- Copper (1)

- Cornices (1)

- Corten (1)

- Cowboy Builders (1)

- Czech Republic, (1)

- Data Centers (1)

- David Hockney (1)

- David Lea (1)

- Digital Twin (1)

- Domus Nova (1)

- Dormer extension (1)

- Embodied Carbon (1)

- EnvironmentalArchitecture (1)

- Flooding (1)

- Future of Housing (1)

- Gandhi memorial museum (1)

- Georgian Extension (1)

- Green Register (1)

- Green infrastructure (1)

- GreenDesign (1)

- History (1)

- India (1)

- Interior Finishes (1)

- Jan Kaplický (1)

- Japandi (1)

- Joinery (1)

- Kitchen Design (1)

- L-shaped dormer (1)

- Land value (1)

- Leonardo Da Vinci (1)

- Lord's Media Centre (1)

- Mapping (1)

- Marseilles (1)

- Mary Portas (1)

- Metal (1)

- Micro Generation (1)

- Mid Century Retrofit (1)

- Monuments (1)

- Mouldings (1)

- Museum Architecture (1)

- Mycelium Architecture (1)

- NPPF (1)

- Nature (1)

- New Build House (1)

- Notting Hill Architects (1)

- Office to Homes (1)

- Office to Hotel Conversion (1)

- Offsite manufacturing (1)

- Origami (1)

- Padel Court (1)

- Party Wall Surveyor (1)

- PeopleFirstDesign (1)

- Place (1)

- Podcast (1)

- Porch (1)

- Prefab (1)

- Procurement (1)

- Public Housing (1)

- Queen's Park (1)

- RISE Team (1)

- Rebuild (1)

- Replacement Dwelling (1)

- ResilientFuture (1)

- Richard Rogers (1)

- Rural New Build (1)

- Sand (1)

- Scandinavian architecture (1)

- Selfbuild (1)

- Skirting (1)

- Slow Architecture (1)

- Small Sites Development (1)

- Solar Shading (1)

- Steel (1)

- Stone Architecture (1)

- Surveying (1)

- Sustainable Basement Extension (1)

- Sustainable Building Systems (1)

- Sustainable Housing (1)

- Sustainable Lighting (1)

- Sustainable Mews House (1)

- Sustainable Padel Court (1)

- Sustainable Retail Store (1)

- Sverre fehn (1)

- UFH (1)

- VR (1)

- Victorian Extension (1)

- Walkable Cities (1)

- West london (1)

- Whole Life Carbon (1)

- Wildlife (1)

- Wood (1)

- architect fees (1)

- architectural details (1)

- arne jacobsen (1)

- avant garde (1)

- basements (1)

- brentdesignawards (1)

- building design (1)

- built environment (1)

- carbonpositive (1)

- cement (1)

- charles correa (1)

- charles eames (1)

- charlie warde (1)

- charteredarchitect (1)

- climate (1)

- climate action (1)

- codes of practice (1)

- collaboration (1)

- covid (1)

- dezeenawards (1)

- drone (1)

- eco-living (1)

- emissions (1)

- finnish architecture (1)

- foundations (1)

- futuristic (1)

- georgian architecture (1)

- glazed envelope (1)

- good working relationships (1)

- green building (1)

- hampstead (1)

- happiness (1)

- home extension (1)

- homesurveys (1)

- imperfection (1)

- independentcinemas (1)

- innovation (1)

- inspirational (1)

- internal windows (1)

- jean prouve (1)

- kindness economy (1)

- kintsugi (1)

- landscape architecture (1)

- lime (1)

- local (1)

- lockdown (1)

- mansard (1)

- manufacturing (1)

- materiality (1)

- modern architecture (1)

- moderninst (1)

- modernism (1)

- moulded furniture (1)

- natural (1)

- natural cooling (1)

- natural light (1)

- nordic pavilion (1)

- northern ireland (1)

- palazzo (1)

- placemaking (1)

- planningpermission (1)

- plywood kitchen (1)

- post-Covid (1)

- poverty (1)

- powerhouse (1)

- preapp (1)

- preapplication (1)

- ray eames (1)

- reclaimed bricks (1)

- recycle (1)

- reuse (1)

- ricardo bofill (1)

- risedesignstudio (1)

- rooflights (1)

- room reconfiguration (1)

- rural (1)

- satellite imagery (1)

- selfbuildhouse (1)

- shared spaces (1)

- site-progress (1)

- solarpvs (1)

- space (1)

- stone (1)

- structuralsurvey (1)

- sun tunnel (1)

- terraces (1)

- thegreenregister (1)

- totality (1)

- wabi-sabi (1)

- January 2026 (2)

- December 2025 (10)

- November 2025 (14)

- October 2025 (8)

- September 2025 (10)

- August 2025 (13)

- July 2025 (23)

- June 2025 (10)

- May 2025 (22)

- April 2025 (16)

- March 2025 (8)

- February 2025 (12)

- January 2025 (6)

- December 2024 (6)

- November 2024 (8)

- October 2024 (5)

- September 2024 (3)

- August 2024 (2)

- July 2024 (2)

- June 2024 (2)

- May 2024 (1)

- April 2024 (1)

- March 2024 (1)

- February 2024 (1)

- January 2024 (3)

- November 2023 (1)

- October 2023 (5)

- September 2023 (7)

- August 2023 (7)

- July 2023 (6)

- June 2023 (8)

- May 2023 (14)

- April 2023 (11)

- March 2023 (8)

- February 2023 (6)

- January 2023 (5)

- December 2022 (3)

- November 2022 (3)

- October 2022 (3)

- September 2022 (3)

- July 2022 (2)

- June 2022 (1)

- May 2022 (1)

- April 2022 (1)

- March 2022 (1)

- February 2022 (2)

- January 2022 (1)

- November 2021 (1)

- October 2021 (2)

- July 2021 (1)

- June 2021 (1)

- May 2021 (1)

- April 2021 (1)

- March 2021 (1)

- February 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (2)

- December 2020 (1)

- November 2020 (1)

- October 2020 (1)

- September 2020 (2)

- August 2020 (1)

- June 2020 (3)

- April 2020 (3)

- March 2020 (2)

- February 2020 (3)

- January 2020 (1)

- December 2019 (1)

- November 2019 (2)

- September 2019 (1)

- June 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (2)

- January 2019 (2)

- October 2018 (1)

- September 2018 (1)

- August 2018 (2)

- July 2018 (1)

- March 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (2)

- December 2017 (1)

- September 2017 (1)

- May 2017 (1)

- January 2017 (1)

- December 2016 (1)

- November 2016 (1)

- September 2016 (1)

- August 2016 (2)

- June 2016 (2)

- May 2016 (1)

- April 2016 (1)

- December 2015 (1)

- October 2015 (1)

- September 2015 (1)

- August 2015 (1)

- June 2015 (1)

- January 2015 (1)

- September 2014 (2)

- August 2014 (1)

- July 2014 (4)

- June 2014 (9)

- May 2014 (2)

- April 2014 (1)

- March 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (1)

- November 2013 (5)

- October 2013 (5)

- September 2013 (5)

- August 2013 (5)

- July 2013 (5)

- June 2013 (2)

- May 2013 (2)

- April 2013 (4)

- March 2013 (5)

- February 2013 (2)

- January 2013 (3)